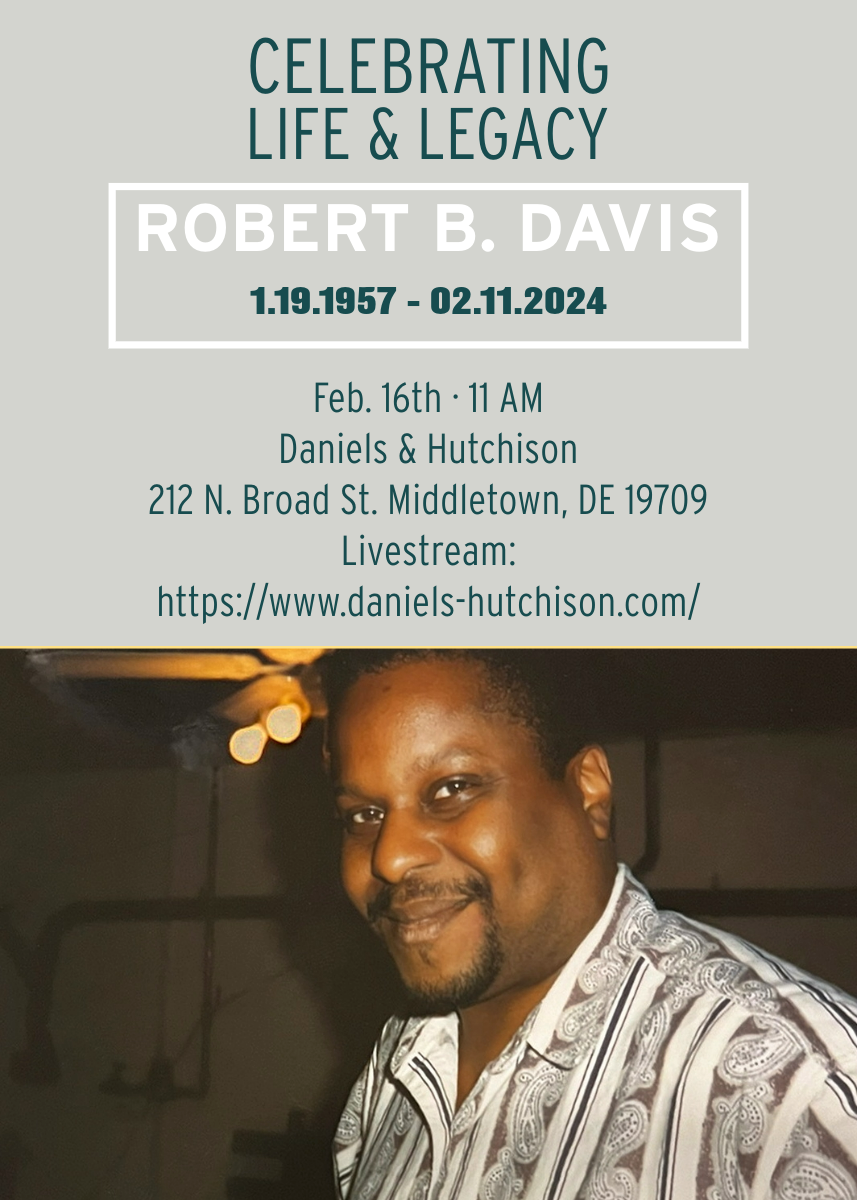

On 2/11/2024, Bob Davis Joined The Ancestors

Out of respect and in honor of his contributions to the music industry, Soul-Patrol will be temporarily unavailable until further notice. We all mourn his passage and the loss of his unique voice to our culture and society.

My Brother, you will be missed.

Michael Davis and The Family